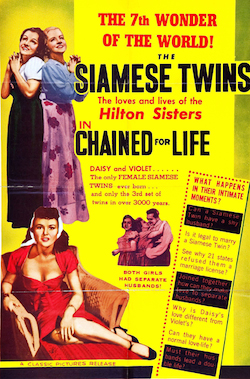

Chained for Life (USA, 1952) 81 min B&W DIR: Harry L. Fraser. SCR: Nat Tanchuck, with additional dialogue by Albert de Pina, based upon an idea by Ross Frisco. PROD: George Moskov. MUSIC: Henry Vars. DOP: Jockey Feindel. CAST: Violet and Daisy Hilton, Mario Laval, Allen Jenkins, Patricia Wright, Norval Mitchell.

In Tod Browning’s 1932 film, Freaks, a man kisses one of the siamese twin sisters, while the other twin visibly enjoys the kiss. This blatantly sexual moment in one way illustrates how Freaks was marketed for years as an exploitation film for its subject matter. On the other hand, Browning’s controversial, shocking yet touchingly beautiful melodrama illustrates how these sideshow attractions, despite their deformities, are people too, and yes, can have natural sexual impulses just like everyone else.

After appearing in Freaks, sisters Daisy and Violet Hilton (who were joined at the hip, yet each had four limbs, and shared no vital organs), spent years in the carnival circuit, and as a musical act (piano-violin duo). They returned to the silver screen one last time for this golden-age exploitation picture, which in typical “roadshow” tradition, is bookended with an authority figure (in this case, a judge) who addresses the viewers about suspending our own moral judgments as we witness the story within.

However, despite the usual accepted liabilities of these poverty row wonders (bad acting, poor production values), all one can rightfully ask is that these films, you know, shock. Since Chained for Life is about one sister’s attempts to marry, the frank sexuality evidenced in Freaks is surprisingly ignored here. It is at heart a rather straightforward melodrama.

The Hiltons play The Hamilton Sisters, a singing act in a failing vaudeville revue. In order to score at the box office, their promoter comes up with the sensational marketing campaign that one of the sisters is to marry Andre (Mario Laval), who is part of the trick-shooting act also featured in the show. (His partner, Renee, played by the tantalizingly sexy Patricia Wright, is not so amused by this arrangement.) Andre courts Dorothy (Daisy), who really does fall in love with the smooth-talking gigolo, but sister Viv (Violet) is less than flattered by Andre, who slyly chisels away her newfound wealth from this publicity stunt. After the marriage, Andre has reached the pinnacle of his popularity, and promptly dumps Dorothy. Viv shoots Andre, and is put on trial for murder. Many states forbid Dorothy’s marriage, because technically it is bigamy, as she and Viv are conjoined. Ironically, they are forbidden to marry just like anyone else, but the court does not hesitate to persecute them as anyone else. The film ends with the judge, indecisive about incarcerating both women or none, asking the viewers what to do.

It seems that the makers were actually trying to do more than necessary for its eventual fate in the roadshow ghetto. Despite the limited budget, the cinematography is crisp, and scenes often play with fluid tracking shots. By comparison, this is an art-house picture for director Harry Fraser, who had previously made countless PRC cheapies. The major plot element where Andre leaves Dorothy is however presented as a newspaper headline. So many vintage B pictures would use this as a money-saving device to avoid filming a scene. However, the decision to not visualize that moment tastefully omits the sisters’ further degradation onscreen. Chained for Life is much more austere than Freaks, but the sensibility is the same: they are stories about people with abnormalities who want “normal” lives. (There is even a jaw-dropping dream sequence, where, with the help of a lens effect and body double, Dorothy envisions herself physically separated from her sister, rising up from the bed they share, and dancing on her own.)

The honourable Judge Mitchell (Norval Mitchell) boldly confronts the viewer with the thought: “No matter what your problems are, they can’t be as bad as theirs”. Indeed. Offscreen, the Hilton sisters were physically abused at a young age by their stepmother, and abandoned much later in life by their promoters, penniless in a strange town, forced to pick up the pieces and start over again. Still, the Hiltons were survivors, and based upon accounts I’ve read, they were apparently very nice people. But in all honesty, actresses they were not. This film is always fascinating to watch because of the unusual subject matter, and because it is easy to sympathize with the Hamilton sisters, but in truth the movie doesn’t transcend its novelty value, as the Hiltons appear tired, glum, and passionless. However, wouldn’t we be, after spending a lifetime of difficulties?

Chained for Life indirectly succeeds in its desire to be more than the quick-buck exploitation picture it was fated to be. While it ends without a proper story resolution, the payoff is in the judge’s dialogue to the viewer: we are forced to evaluate many things we have just witnessed.