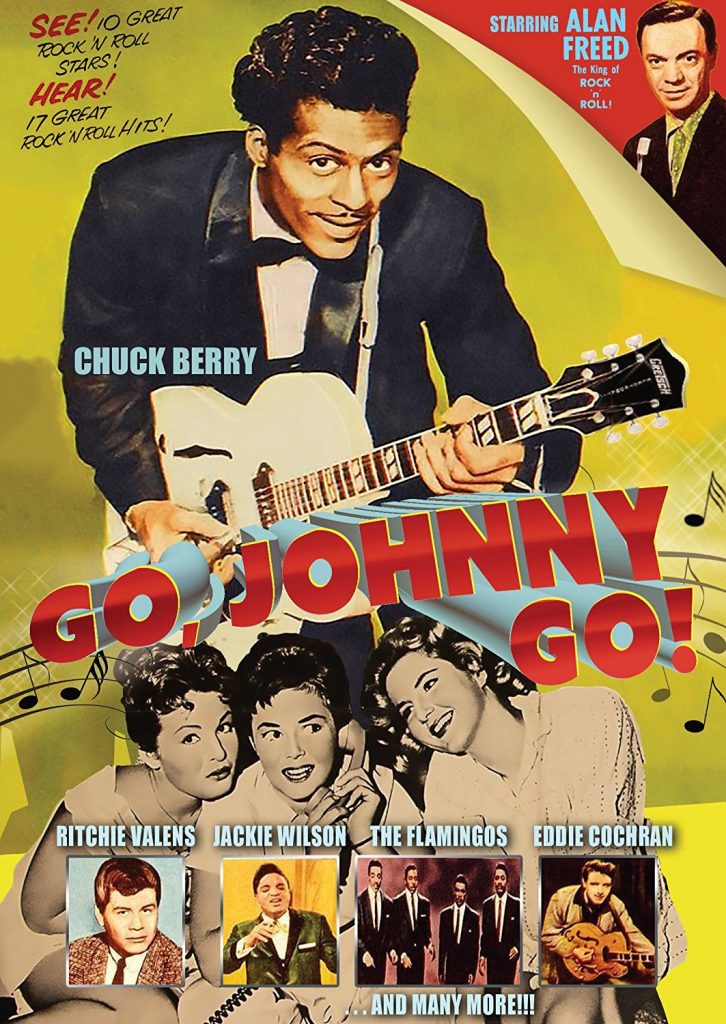

Go, Johnny, Go! (USA, 1959) DIR: Paul Landres. SCR: Gary Alexander. PROD: Hal Roach, Jr. MUSIC: Leon Klatzkin. DOP: Jack Etra. CAST: Alan Freed, Jimmy Clanton, Sandy Stewart, Chuck Berry, Ritchie Valens, Eddie Cochran, Jackie Wilson, Joann Campbell, The Cadillacs, The Flamingos. (Hal Roach Studios)

The final Alan Freed vehicle, following Rock Around the Clock (1956), Don’t Knock the Rock (1956), Rock, Rock, Rock! (1956), and Mister Rock and Roll (1957), is arguably the best, if because the plot (however derivative) is better written, and the musical numbers are better integrated with it. Singer Jimmy Clanton plays the slightly obnoxious Johnny Melody, who has won yet another talent contest. Johnny has a history of juvenile delinquency, which will come back to haunt him, but redemption is always a key theme in Alan Freed’s pictures.

Chuck Berry performs “Johnny B. Goode” and “Little Queenie”, but also appears as an actor- a lot of fun in a rare dramatic supporting role, even if he plays himself. (It would be quite a year for him on film, as the documentary Jazz on a Summer’s Day shows his controversial appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival. And speaking of jazz, Dave Brubeck plays uncredited piano on “Little Queenie”!) In addition, we get some valuable performances on film by Jackie Wilson (“You Better Know It”), Joann Campbell (“Momma Can I Go Out”), The Cadillacs (“Jay Walker”) and The Flamingos (“Jump Children”). But this film is especially noteworthy for its rare footage of Eddie Cochran (who plays the creepily prophetic “Teenage Heaven” at a coffeehouse) and Ritchie Valens (with “Ooh My Head”)… both of whom would have untimely deaths. Sandy Stewart (a young ballad singer) plays Johnny’s girlfriend, and also gets to croon “Playmates”, who stands by her man through all the misunderstandings. Once again, Freed comes to the rescue by saving Johnny’s potential singing career by taking the blame himself for the kid’s throwing a brick through a window. Because he is Alan Freed, everything will come out all right. It is hilarious seeing Freed pretending to be drunk when the cops arrive after the smashed window sets off an alarm. Never much of a performer in his pictures (as evidenced by the way he tries to sing along to a number in Rock, Rock, Rock!), this may be his finest moment as an actor.

Seeing Freed getting picked up by the police in his final film is a chilling precursor of course to the payola scandal that destroyed his career. In the 1950’s, disc jockeys were accepting cash or gifts by record producers in exchange for getting their singles on the air. Almost everybody was doing it, however one could say that Freed was the one who most paid for it, as the law used him as an example for all the rest. It could be suggested that Freed’s arrest was the first rock and roll conspiracy. Because he was too powerful a voice, the God-fearing conversative majority still perhaps perceived him as a threat to their children, or America as a whole (if we are to remember that this was still the age of segregation). Alan Freed, on the air, on stage and on film, broke racial barriers with integrated musical acts and audiences. Even so, he was no stranger to controversy. In fact, his TV show was pulled from a Southern market because it featured Frankie Lymon dancing with a white girl.

In John Jackson’s superb book, Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock, one sees a photo of Freed shortly after the payola scandal, and it is incredible how much he had visibly aged in one year from his appearance in Go Johnny Go. Although Freed found sporadic employment over the years, his career never recovered from the scandal. He died in 1965 from cirrhosis of the liver, but it has been suggested that he really died of a broken heart. At the end of the excellent biopic American Hot Wax, where Freed’s mantle is undone not by payola but by a riot at one of his shows, he declares “You can stop me, but you can’t stop rock and roll.” Time has obviously proven him right.