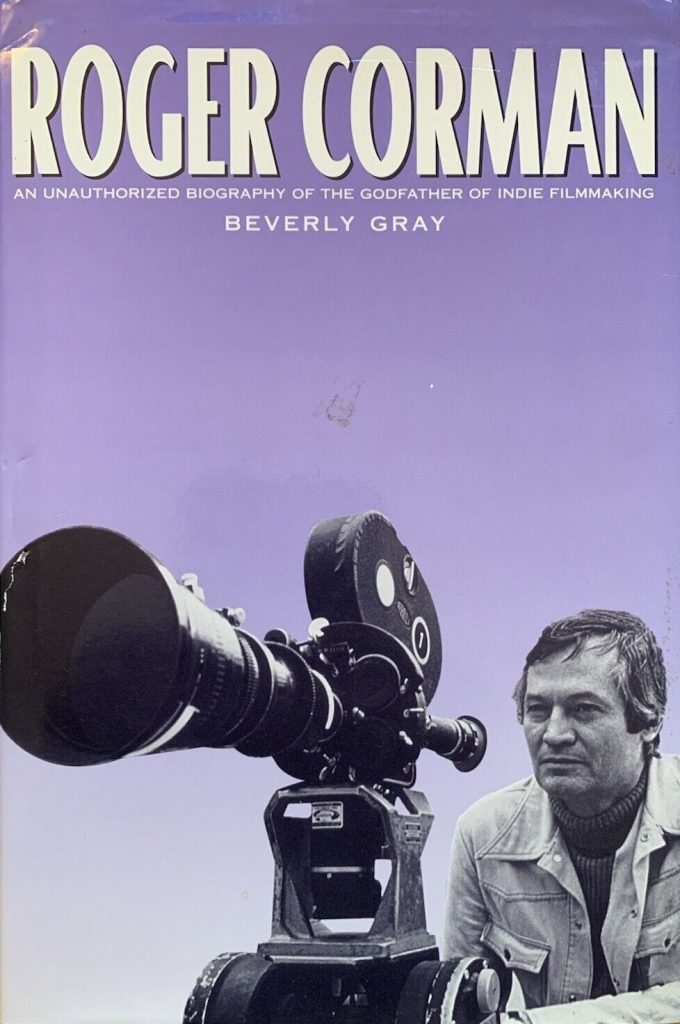

Roger Corman: An Unauthorized Biography of the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking

Beverly Gray

Renaissance Books; 2000

This terrific read was recently re-released with a new title, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches and Driller Killers. It seems that the publishers decided to make this as enticing as any of the sensational titles of Roger Corman’s 1950s potboilers, thus increasing its market potential. In that case, this is truly a book keeping in the spirit of its subject matter.

Beverly Gray worked at Roger Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons studio in the 1990s, scripting and producing such fare as Hellfire and Fire on the Amazon. Corman became a more prolific producer than ever at Concorde-New Horizons, however it must be said that much of that output is generic and forgettable. As ever, Corman was a step ahead of the majors by realizing the potential of home video, but curiously he was behind the times in trends. For instance, Munchies was a late addition to a subgenre of films like Ghoulies or Critters, cashing in on Gremlins, which was, ironically, made by Corman’s former employee, Joe Dante. As a result, the time at Concorde is the least documented chapter of Corman’s career. This book is vital for filling that career gap in print, by giving a sense of life at the Concorde factory, and more.

While Corman’s own book is a more involved recounting of such an extraordinary career, Gray’s book is rare for depicting Roger Corman as a very complex man, favouring nuance over narrative to shape this portrait. For instance, Ms. Gray draws upon Corman’s early career training as an engineer, applying that sensibility to his personality and his prolific career. This analogy especially comes to life in documenting the wild times at the Concorde lot, in its breezy description of the “churn ‘em out” lifestyle of cranking out one light-headed genre picture after another, always with the mantra: “More nudity.”

With anecdotes by such Corman alumni as Charles B. Griffith or Howard R. Cohen, the correlation between Corman and machine comes even closer with observations of his sometimes cold and distant demeanour, and his graduation (or is that demotion?) to an assembly-line product that exists purely to make money. In keeping with Corman’s own byline of making a hundred movies and never losing a dime, stories of Roger’s customarily penny-pinching ways abound, but most interestingly, it is revealed that Roger Corman doesn’t seem to reward himself for all of his hard work in shrewd cost cutting, niche marketing, and profit margins. Such odd stories as his refusal to spend money on a plane ticket or (my favourite) on cleaning the rugs at the Concorde office allude to the curious nature in which Corman seems to punish himself.

While Gray paints a less than flattering portrait of her former boss, it is not done in a scandalous way. Instead, she seems to portray Corman as a frustrated man who secretly aspires to aesthetic greatness, yet nonetheless accepts his fate to keep making one generic product after another. (One can see a glimpse of this earlier in Corman’s career at New World Pictures- while producing a lot of drive-in exploitation, he also acquired foreign-language art films for domestic distribution. This can be seen as another clever marketing ploy à la Corman, but on the other hand, his distribution of pictures by such masters as Ingmar Bergman can be also be read as a personal kind of artistic atonement.) Perhaps that is the price paid for his independent streak, insistent upon making movies in his own system than under the umbrella of anyone else’s.