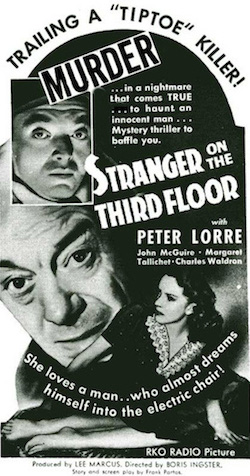

Stranger on the Third Floor (USA, 1940) 62 min B&W DIR: Boris Ingster. PROD: Lee S. Marcus. SCR: Frank Partos, Nathanael West. MUSIC: Roy Webb. DOP: Nicholas Musuraca. CAST: Peter Lorre, John Mc Guire, Margaret Tallichet, Charles Waldron, Elisha Cook Jr., Charles Halton. (RKO Pictures)

This RKO B-picture is commonly considered as the first American film noir. At first glance, it more fits in with the 30s cycle of newspaper-crime pictures. However, as the film progresses, the characters’ misanthropy and dementia, plus a moody lighting style clearly divorce it from the 1930s wisecracking formula.

John McGuire plays reporter Mike Ward, who is the key witness in a trial for a cabbie (played by noir’s favourite fall guy, Elisha Cook Jr.) who is accused of murder. Ward’s circumstantial evidence renders the man a death penalty sentence. However, he begins to doubt his own testimony, because perhaps Cook could very well have been an unwitting bystander in the case. Still, Ward is assured that he did the right thing. One hardened reporter tells him, “There’s too many people in the world anyway.”

One night, he notices a strange little man outside his building, and then inside on the stairwell. Once inside, he realizes that he can’t hear his next door neighbour (“who is less than human”). Then in the film’s highlight, Ward falls asleep, and there is a stunning dream sequence in which he is held accountable for murder. He is in a representative, larger-than-life courtroom with cucoloris patterns on the wall. In the tradition of the German Expressionist films from which it takes its cue, this sequence has mattes of the heads of the people who condemn Ward- even the doomed cabbie is one of the persecutors. Everyone points at Ward, in a stilted figurative way, which seems pulled from a UFA film in the 1920s.

Ward awakens and goes next door to find his hated next-door neighbour with his throat slashed- the same M.O. of the murder for which the cabbie is condemned. Thus, Ward believes that the little man with the scarf is the killer. His fiancée Jane (Margaret Tallichet) helps him find the stranger.

Although this film has perhaps a coincidence or two too many, that perhaps is the price it pays for being an hour-long B noir. However, there is an exceptional amount of mood and style. As Ward becomes more emotionally involved in the case (thus, more culpable), the film’s look becomes more expressionistic. Aside from the amazing dream sequence, this movie makes marvellous use of shadow and light: slash lighting to partially illuminate faces, hard key lights and and long shadows on the staircase, reflections of rain on the window spotting the characters. This perfectly compliments the paranoid mood, as Ward becomes more unglued, and for that matter, it reflects the irrational, inhuman world in which Ward lives- if anything, this excursion into the dark side makes him realize his own base behaviour.