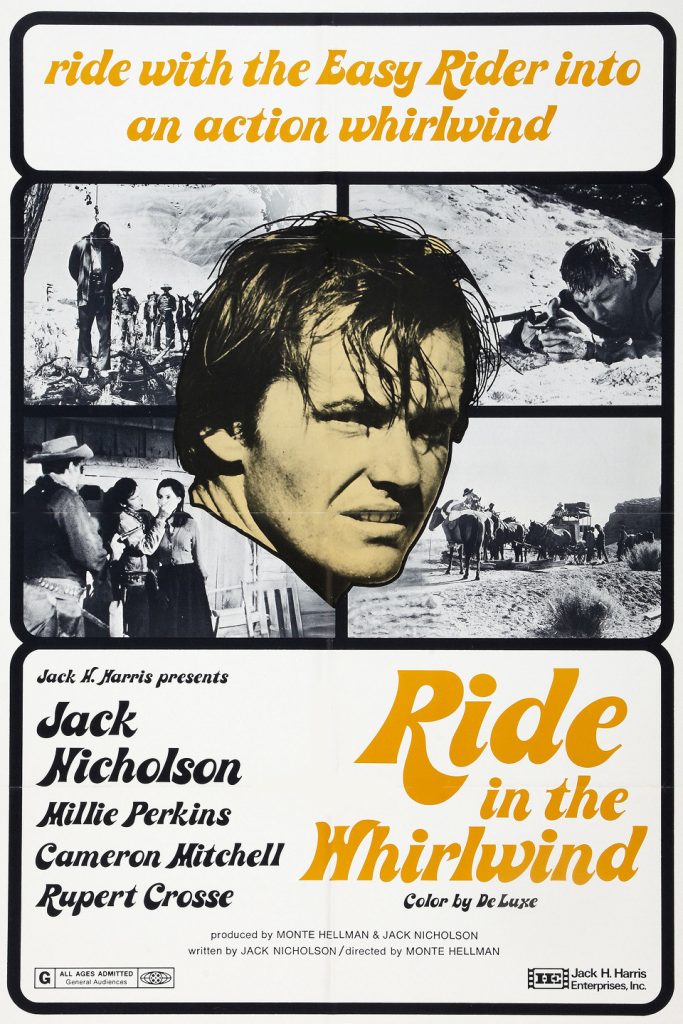

Ride in the Whirlwind (USA, 1966) 82 min color DIR-EDITOR: Monte Hellman. PROD: Monte Hellman, Jack Nicholson. SCR: Jack Nicholson. DOP: Gregory Sandor. MUSIC: Robert Drasnin. CAST: Cameron Mitchell, Jack Nicholson, Tom Filer, Millie Perkins, Katherine Squire, George Mitchell, Harry Dean Stanton, Rupert Crosse, Gary Kent. (Jack H. Harris Enterprises; Favorite Films)

Amusingly though accurately coined as “Kafka on the range” in Steven H. Scheuer’s perennial reference guide, Movies on TV, Ride in the Whirlwind was one of two westerns shot back-to-back in Utah by Monte Hellman in 1965, as a “two for one” package deal for Roger Corman. Sharing much of the same crew (including excellent colour cinematography by Gregory Sandor) and some principal cast members (Jack Nicholson and Millie Perkins appear in both), Whirlwind, and its companion film, The Shooting, share the common theme of characters thrown into situations beyond their control or understanding.

Three cowhands, Vern (first-billed Cameron Mitchell) Wes (third-billed Jack Nicholson) and Otis (Tom Filer), on their way to a cattle drive, are invited by an outlaw gang to rest for the night at their shack. We recognize these desperadoes from the stage robbery in the film’s opening. Once a posse arrives next morning to start shooting up the place, the three men decide to make a run for it to save their own skins. Otis is killed in the escape to freedom, but Vern and Wes elude the posse by hiding in a cliff for the night, and then next day seek temporary refuge in a homestead until they plan their next move. The leader of the posse had already visited the house, peopled by Evan and his wife Catherine (played respectively by real-life couple, George Mitchell and Katherine Squire) and their grown daughter, Abigail (second-billed Millie Perkins), but because he is attracted to Abigail, he returns to the homestead, and fate intervenes on Wes and Vern once again.

Of the two westerns, The Shooting perhaps leaves the greater impression as it is more abstract and visually striking. (A better analysis of that film will be left to its own review.) Ride in the Whirlwind, on the other hand, may be the more satisfying film for casual viewing at the 2 AM time slot for which it was fated. Its narrative is less elliptical and therefore less demanding. These were just the kinds of titles you would discover in the late night listings of TV Guide, and would have to look up in one of those many movie reference books we all had back in the day. (And yes, these are the perfect kinds of films to stumble on at 2 AM… that time where the film you discover seemed to be made just for you.)

The films enjoyed acclaim and healthy theatrical releases in France (naturally). However, in the United States, they failed to find domestic distribution and were instead sold to a television package. Their eventual re-discovery through late-night television – and later, home video – was no doubt helped by the later fame of Monte Hellman (after his breakthrough film, Two-Lane Blacktop) and especially after Jack Nicholson became a superstar. Nicholson’s face would appear on the box art of the films’ numerous budget VHS or DVD releases (giving the mistaken impression that the titles were in public domain), even though he was a supporting player in either film, and yet was hardly a household name when they were originally produced. (Think for instance, how often Nicholson’s face was featured on cover art for the numerous video releases of Little Shop of Horrors, although he was in one scene.)

Most of cinema history is documented in hindsight. Time is the greatest ally of a film enthusiast, who can re-evaluate the artistic or historical significance of works that were overlooked in their initial releases. At this remove, we now see how these westerns were major precedents to the careers of Jack Nicholson and Monte Hellman, and to the “revisionist” American westerns that would soon follow.

Before collaborating on these pictures, Jack Nicholson and Monte Hellman had also worked together on two back-to-back films shot in the Philippines: the war drama Back Door to Hell, and the espionage adventure Flight to Fury (still one of my favourite “Hellman”s). In addition to acting and various production duties, Nicholson also wrote the screenplays for Flight to Fury and Ride in the Whirlwind, which suggest that he was striving for something unique beyond the parameters of genre conventions. His screenplays for Bob Rafelson’s Head and Roger Corman’s The Trip further give evidence that Jack Nicholson was as unique a talent on paper as he was on screen. After the poor reception of Drive, He Said (1971), which he directed and co-wrote, he sadly never went back to the typewriter.

Monte Hellman is an auteur in the truest sense, as his body of work (within or without Hollywood) has a consistent tone and pace. Although his films are written by others, he seems attracted to scenarios of hapless characters caught in a puzzle. (It is small wonder he wanted to direct Quentin Tarantino’s screenplay for Reservoir Dogs, but remained an executive producer). The existential, unconventional antiheroes of Rudy Wurlitzer’s Two-Lane Blacktop, Charles Willeford’s Cockfighter, Nicholson’s Ride in the Whirlwind, and Carole Eastman’s The Shooting, all ponder how they got here, and wonder where they’re going on their self-styled roads to nowhere (to reference a later title in Hellman’s filmography).

While The Shooting features many of the figurative, symbolic devices that would encourage film critics to drain a lot of ink, Whirlwind really has one such moment, early in the film when Vern, Wes and Otis encounter a hanged man. This moment presages the fates of our characters, but truthfully it is a matter-of-fact representation of their frontier world view that life is fragile and death is easy.

Because these westerns didn’t perform well in their own country, one hesitates to say they “influenced” the later American westerns, but they are noteworthy early films to deglamourize the cowboy myth. Nicholson based his screenplay on some frontier diaries he read, and as a result the people and the plotting in Whirlwind are antithetical of the John Wayne-Randolph Scott stereotype. Filer’s character, whose physicality and wardrobe most resembles the standard movie cowboy, gets killed early on, if to remind you that this isn’t the kind of western you grew up watching. This is a feature-length narrative given to the offbeat characterizations that would last one reel in a Hollywood backlot western, if at all. Dust and dirt are like wardrobe and makeup. The stagecoach gang is multiracial, featuring Rupert Crosse (from Shadows) in a role free of stereotype: his silent closeup during the posse shootout speaks out! Harry Dean Stanton could easily have been overplayed his role as the outlaw leader with the eyepatch, but role is as low-key and matter-of-fact as everyone’s.

The slow pace common to Hellman’s films certainly befits these frontier narratives, where life itself was slow. As in Billy Two Hats (1973), where an unusual amount of screen time is spent by watching a sunrise or loading a buffalo gun, most of the action on display is in the details of scaling a cliff or chopping a log. These characters are full of the quirks that would’ve been cut out of a conventional shoot ’em up. They fumble, they’re irritable (Nicholson convincingly portrays the everyday tedium of frontier life, and the little games they play to pass the time), and they’re perhaps half-mad, as one would need to be to live in the godforsaken landscapes on display here. And yet, the principal characters are portrayed in shades of grey. The outlaws in the opening robbery (featuring early stunt work by the legendary Gary Kent) are later seen to be polite, opening their home to the trio of cowpokes; even the homesteaders act neighbourly to Vern and Wes, though they might well be robbed by them. Although Vern and Wes are innocent men, they must resort to evil doings to ensure their survival.

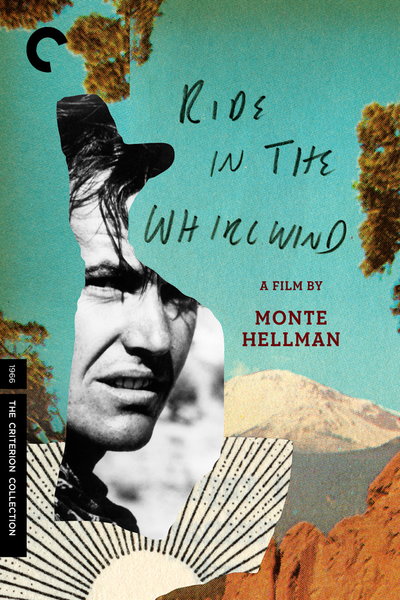

However we viewed these films back then, you still could tell they “had something”. For instance, I first saw Ride in the Whirlwind as a “99 cent rental” VHS, among the many cheap titles gathering dust in corner stores and gas stations throughout my home town, that would be offered to rent for cheap to entice daredevil viewers like yours truly. After reading about these two movies for years, that viewing did not disappoint, because the striking colour and visual compositions were still retained in this presentation, underscoring their unusual narratives. But, if you have a choice, all those so-called PD versions can now be retired, thanks to Criterion’s excellent DVD release, which combines both films, restored to their proper aspect ratios (after we had spent decades enjoying them in full-frame transfers on home video or late-night television), and is loaded with extras, especially interviews that Monte Hellman conducts with Millie Perkins, Harry Dean Stanton and others.

Gallery