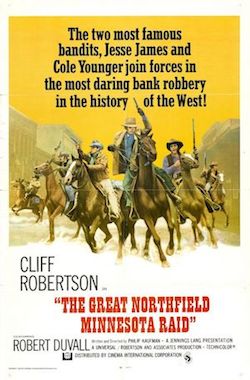

(USA, 1972) 91 min color DIR-SCR: Philip Kaufman. PROD: Jennings Lang, Cliff Robertson. MUSIC: Dave Grusin. DOP: Bruce Surtees. CAST: Cliff Robertson, Robert Duvall, Luke Askew, R.G. Armstrong, Dana Elcar, Donald Moffat, John Pearce, Matt Clark, Elisha Cook Jr., Royal Dano, Barry Brown. (Universal Pictures)

An early scene, in which outlaws Jesse and Frank James use their own “Wanted” posters as outhouse toilet paper, should tell you what to expect in this eccentric account of the infamous 1876 bank robbery, which spelled disaster for the James-Younger gang, as Northfield citizens took up arms to thwart their attempt, resulting in several of the bandits being killed or imprisoned, and dissolution of the famed outlaw gang.

Most viewers would probably have been contented with a straight-up account, like for instance the TV movie The Last Day, which documents the fateful last robbery of the Doolin-Dalton gang. Instead, this feverish, lampoonish hippie western sticks to history only in theory, and delivers a picture that is wildly diverse in style. Seen at this remove, you understand why Philip Kaufman was fired by Clint Eastwood from The Outlaw Josey Wales. Kaufman was too radical a filmmaker to do a simple star vehicle.

The writer-director presents the James-Younger gang as far removed as one could get from Tyrone Power and Henry Fonda. Although the outlaws are soon to receive amnesty, they nonetheless make the expedition from Missouri to Minnesota because one night in what looks to be a sweat lodge, Jesse James (Robert Duvall in this silly goatee) has a vision about money in the north. This scene is also crucial because it features Cole Younger getting a bullet wound treated by an unconventional method. (In fact, the regularity in which Younger is shot becomes a black joke worthy of Buñuel.) The doctor who removes the bullet by hand treats the practice as though it were a supernatural ritual. Kaufman in fact gives the entire film an unnatural quality—especially in comparison with more classical westerns from the 1950s and 1960s. The camera is often treated like a character (at one point, stones are thrown at the lens!)- the long hand-held and POV shots add to the hallucinatory feel. Often shot in selective focus, in which the foreground is hazy, the west is depicted as some strange netherworld, that it is small wonder that every character in this film is strange.

As in the film Bad Company, released the same year, people would have to be insane to continue living in the frontier. Although Jesse James has colloquially been referred to as an “American Robin Hood” (one time he does say they have never robbed an honest man), this film does not portray the gang as a bunch of anti-establishment vanguards, which would appeal to the early 1970s counterculture. Instead, their twangy demeanour reveals them as unwashed, uncouth, though colourful savages. Clell Miller (played by R.G. Armstrong) joins the gang’s crusade to the north because he’s tired of “shoveling mule shit”; Jim Younger (Luke Askew) is always hiding the lower part of his face behind neckerchiefs, or most often, a glued-on mule’s tail for a moustache; and then there’s Cole Younger (delightfully played by Cliff Robertson, who steals the film), who is the actually the most human (spelled: civil, dignified) of the bunch- a pipe-smoking waxing aristocrat who is enamoured of all new things mechanical- be it a metal toy or a steam-powered organ. Oh yes, he always wears a bulletproof vest, which has more than its share of impact marks.

After the disastrous robbery attempt, the disgruntled Northfield citizens who take the law into their own hands, are also revealed as a bunch of goons, albeit in better clothing. They indiscriminately lynch any suspicious character in their view- using the bank robbery as an excuse to wipe out so-called evildoers once and for all. This bit of manipulation of course makes our scruffy outlaws slightly more likeable. However, like many films made in the age of “the new western”, the line between good and bad is cloudy. The picture focuses more on Cole Younger than the James brothers (in fact, Frank James is nearly invisible)- in part, I’m sure, because Cliff Robertson co-produced the movie. However, his character is representative of the way the west was changing. Cole embraces change, typified by his wide-eyed wonder of things such as a steam-powered tractor. (The other boys, in their typically redneck ways, cower from the invention, as though they’re seeing a demon from the netherworld.) In the interesting ending, Younger brashly shows off his punctured vest while paraded down the street in a cage to the cheers of the Northfield citizens, scored by that ever-present street organ, turning the moment into a circus act. The classical image of the gunfighter has become a museum piece, or novelty act. History records that Cole Younger would serve a lengthy prison sentence, and would be released into the 20th century- into the brand new world he was always embracing.