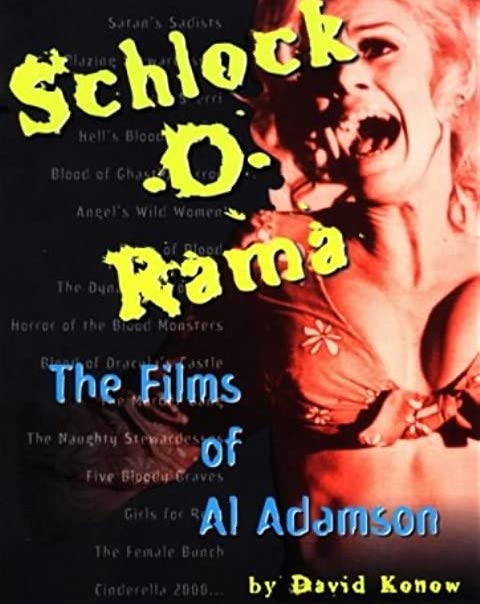

Schlock O Rama: The Films of Al Adamson

David Konow

1996; Lone Eagle

It goes to show that if someone makes enough films, quality or otherwise, someone will write a book on them. Well, just based on the introduction of this book, I want to invite this author over for a barbecue, because I can relate to him so well. A major reason why he wrote this book about Al Adamson in the first place is because Leonard Maltin gave so many of his films a BOMB rating in his annual movie ratings guide, so David Konow rented all of Al’s films to see what the fuss was all about, and became entranced by their, uh, uniqueness.

Like the author, I too grew up watching the works of Adamson et al on the late late late show, and so he is writing in my figurative backyard. Truthfully, I’ve never been a fan of Adamson’s work- what films of his I have seen have been mean-spirited, ugly and cold. I always felt that his slapped-together opuses were snide towards the people that paid money to see them. However, I confess there is a perverse attraction to them. I saw Dracula Vs. Frankenstein (his best-known film) on The Cat’s Pajamas– and it was so horrid and appalling, I watched it twice. Having read Konow’s wonderful book on the universe of Adamson, I want to go out and rent all of Al’s films again.

Schlock O Rama chronicles some of the corners that Adamson and his faithful producer Sam Sherman had cut in order to keep costs down on their already skimpy budgets. Most famously, Al got Kentucky Fried Chicken to provide craft services to the entire shoot of Hell’s Bloody Devils because he made a deal with Colonel Sanders to give him a cameo appearance in the movie! Sometimes your head spins at how cheap these films really were. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (who had a long career in exploitation films before he became part of the Hollywood echelon) recounts how at the end of one shoot, Al paid everyone… from money he just collected from his paper route!

Adamson’s products are not indicative of the feel-good kind of memories which we romantically attach to old B movies. If, for instance, Ray Dennis Steckler’s films are rock and roll parties and Saturday matinees, Adamson’s films are the Manson Family, the Hell’s Angels and LSD. They reflect the dark side of the 1960s that people choose to forget in their day-glow reminisces of the period. Be it his horror films, biker epics, blaxploitation fare or even his westerns, his universe is full of violence and danger. (That is not to suggest that Al’s films are racist or sexist: if anything, female and black characters are often the victorious ones.) Frighteningly, the Manson family peskily hung around on set just before the Tate-LaBianca murders, as one film was shot on the Spahn ranch where they lived- one member is even seen in the background!

Which brings us to why I get a bad taste in my mouth over the Adamson-Sherman enterprise. Anything for a buck. After the murders, they exploited the Manson Family’s involvement in the films to sell more tickets! This is the darkest aspect of the otherwise amusing ways in which these two would market a film. In Adamson’s best-known period of the late 1960s and 1970s, films were endlessly recut and retitled to make a brand new movie to fill drive-in bills. In their day, patrons would be ticked off because they paid money to watch something they already saw. Somehow this fits into the guilty pleasure one gets from exploitation cinema- we know we’re paying money to see something that probably will suck; sometimes being screwed is consensual. One has to shake one’s head and be amazed by their intrepid dealings, despite how negligible they are. Plus, for the masochistic viewer, Adamson’s films are filled with famous names past their glory days -Scott Brady, Broderick Crawford, Yvonne DeCarlo, Kent Taylor, Russ Tamblyn, and of course John Carradine- who briefly appeared in many of the films so they could nonetheless put big names in the marquees.

Despite the very comical accounts from people like his faithful cameramen such as Gary Graver, or supporting players Marilyn Joi and Russ Tamblyn, the book is a ghost song to a bygone era. Nowhere is this better emphasized than in the last two chapters. The Adamson enterprise abruptly halted when the major studios took over the drive-in circuit (before they became condo sites, that is). Plus, during his long hiatus, Al tended to his beautiful wife, actress-dancer Regina Carroll (who graced a few of his productions), who subsequently died of cancer. Adamson’s projected comeback after her death was cut short due to his own murder. In something as ghastly as one of his own films, Adamson was murdered by his contractor, and his body was encased in concrete under his house! Konow was already putting together this book with Al’s cooperation, until Adamson’s murder added an uncomfortably ironic reel life/real life duality to this project.

Part showman, carnival barker and snake oil salesman, Adamson managed to make a career out of these dour skid-row entertainments. Anyone who could pull that off for so long one must admire, even though one questions the product they were hustling. In the filmography, one is amazed by the vast number of films one hasn’t seen- he was always working! I guess that’s part of the charm of the carnival barker, and part of the life of an exploitation filmgoer- I’m interested enough in his body of work to go and hunt it down again, even though I know the bowling pins I’m supposed to knock down are glued to the stand.