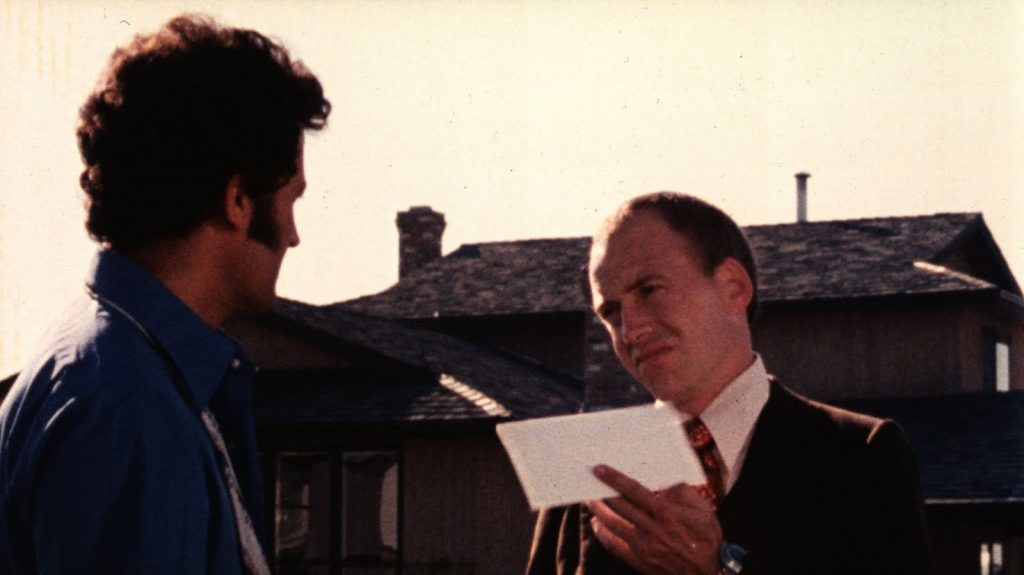

Skip Tracer (Canada, 1977) 95 min color DIR-SCR-EDITOR: Zale Dalen. PROD: Laara Dalen. MUSIC: Linton S. Garner. DOP: Ron Orieux. CAST: David Peterson, John Lazarus.

During Canada’s tax shelter movement, when dentists and lawyers were encouraged to make movies with a 100% tax write-off, there were still films that didn’t attempt to be the ersatz Hollywood commercial product that was the norm for tax shelter fare. Take Skip Tracer. This unsettling work opened in 1977 to good reviews on the festival circuit, and then, like all Canadian cinema not done by David Cronenberg, didn’t play well at the box office and slipped away, only to be occasionally revived in second-run venues whenever they do a “Best of…” Canadian retrospective, or as CanCon filler on TV. To date, its only home video appearance was on VHS, with the alternate title, Deadly Business.

Skip Tracer is guerrilla filmmaking at its finest. Shot in roughly a month in the fall of 1976 for $145,000.00, this is a lean, mean movie that unsparingly depicts the dirty things people do for a living. Our “hero” is John Collins (Peterson), a repo man who is in a slump. Usually he is the top man of the year in terms of successfully collecting from delinquent debtors. Collins is a quick-witted cynic who seldom finds anything cheerful in his life. David Peterson plays the role a little over the top, perhaps how Collins would act, to disguise his shallow interior. During his downtime, he shows the ropes to an eager young man, Brent Solverman (Lazarus). Through Collins, we learn that heartlessness is the trick to surviving this business.

Sometimes Collins doesn’t practice what he preaches, in moments when his humanity precedes his call of duty. In one scene, he subtly tells a client to get a loan through a bank instead of through his firm, because he would get charged a lower interest rate. Perhaps this is why this former top dog of the company no longer has a private office, and his effects have been moved to the common, open concept section of the bureau. Collins is as much at war with the office competition as the people who owe money.

Skip Tracer’s success is often due to its constant element of surprise, and lack of pat solutions. Most tellingly, Collins gets stabbed by one of his debtors, but the identity of his assailant remains unsolved. His consistent efforts to collect from a recurrent foil named Pettigrew, ends in a shocking resolution. A more conventional film would naturally have the identity of the stabber resolved, or Collins’ new partner would come to his rescue. Rather, Brent practically disappears from the plot, just as life could have it. After he recuperates from his wound, Collins adapts a “fuck you” approach to everyone: the clients who always give him the runaround, and the agency that is always screwing him.

This striking film, -written, directed and edited by Zale Dalen and produced by his wife Laara- is mostly shot in long, single takes, adding to the element of surprise: the frame is so wide that anything could intervene. One memorable segment features Collins hammering away at a drain pipe where one of his deadbeats is hiding. It is so uncomfortable to watch, as there are no safe cutaways: you are forced to watch the dehumanization in his daily routine. But also Dalen has a great eye for detail: occasionally he will cut away to people’s involuntary gestures, so you can really tell what they’re thinking behind all that tough talk.

Filmed by Ron Orieux in muddy browns and heightened whites, Skip Tracer has a washed-out look that compliments the gritty material. The less picturesque avenues of Vancouver become an impressionistic essay about our hero’s confining world. His realm is a claustrophobic office space with papers a mile high, a tiny bachelor apartment, seedy strip joints, bungalows with crying kids and expensive TV sets, and flat undeveloped suburbia with fancy houses in which ten-cent millionaires hide behind the curtains.

Skip Tracer still puts to shame most of what is called Independent cinema today. It also puts to shame the typically mitigating factors that affect much of our country’s artists. After the critical success of this film, Zale Dalen’s follow-up picture, The Hounds of Notre Dame, was poorly handled, and has largely remained unseen, even in the usual slipshod ways in which Canadians must view their own cinema. Dalen’s resume of sporadic feature films includes the futuristic punk fantasy Terminal City Ricochet, and the unreleased ensemble romantic comedy, Passion. Like many of our filmmakers who remained north of the border, he had spent much of his career directing television, as the feature films got fewer and further between.

Nonetheless, Skip Tracer is a dark horse milestone in Canadian cinema that didn’t deserve its early retirement from the limelight. But once seen, it is an unsettling piece that one never truly shakes off. However you can see this, Skip Tracer is essential viewing.